In my previous posts, I mostly wrote about the advantages of being an anti-self: we have seen that people with antithetical abilities are all exceptional, talented characters, strongly connected to art and high thinking. But Yeats firmly believes that the antithetical impulse may grow a fanaticism and a terror, and may oppress the ignorant and the innocent. This side of the anti-self and the Pirandellian personaggio is nicely presented in Six Characters and in The Player Queen. In my previous post, I deliberately omitted the most important personaggio who becomes the most dangerous and dominant figure, and the sole stage manager in the play.

In my previous posts, I mostly wrote about the advantages of being an anti-self: we have seen that people with antithetical abilities are all exceptional, talented characters, strongly connected to art and high thinking. But Yeats firmly believes that the antithetical impulse may grow a fanaticism and a terror, and may oppress the ignorant and the innocent. This side of the anti-self and the Pirandellian personaggio is nicely presented in Six Characters and in The Player Queen. In my previous post, I deliberately omitted the most important personaggio who becomes the most dangerous and dominant figure, and the sole stage manager in the play.

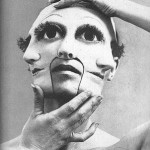

In Six Characters, there is one personaggio who emerges even from the other five personaggio figures. This character is the Step-Daughter who, as Marco Ariani puts it, has the greatest exhibitionist aggression and tension in the play. It is her aggression, tension, passion, cruelty and feigned insanity that make her superior to the other personaggios. She relentlessly pokes fun at the Manager and his actors, and prevents the Manager from starting the rehearsal. She acts as if she were the director: it is she who gives advice to the actors and the Manager, and gives orders as regards the setting. At one point the Manager asks her: “Excuse me, but are you the Manager, or am I?” And she is the real director, indeed, who by virtue of her passion and aggression oppresses not only the personas, but her fellow personaggios as well.

the Step-Daughter who, as Marco Ariani puts it, has the greatest exhibitionist aggression and tension in the play. It is her aggression, tension, passion, cruelty and feigned insanity that make her superior to the other personaggios. She relentlessly pokes fun at the Manager and his actors, and prevents the Manager from starting the rehearsal. She acts as if she were the director: it is she who gives advice to the actors and the Manager, and gives orders as regards the setting. At one point the Manager asks her: “Excuse me, but are you the Manager, or am I?” And she is the real director, indeed, who by virtue of her passion and aggression oppresses not only the personas, but her fellow personaggios as well.

Decima in The Player Queen also deprives the Stage Manager of his role and starts to direct her own play. Her fellow actors see the daemon in her eyes, and therefore cannot trust her. Yet Decima manipulates all of them. The Manager is unable to stop her mad behaviour, and this is why Nona (Decima’s rival) reprehends the Manager: “She is doing it all to stop the rehearsal, out of vengeance; and you stand there and do nothing.” The Manager cannot act, nor can the actors and actresses, because Decima plays with them as if they were her puppets—nobody can prevent her from becoming the player queen.

Decima in The Player Queen also deprives the Stage Manager of his role and starts to direct her own play. Her fellow actors see the daemon in her eyes, and therefore cannot trust her. Yet Decima manipulates all of them. The Manager is unable to stop her mad behaviour, and this is why Nona (Decima’s rival) reprehends the Manager: “She is doing it all to stop the rehearsal, out of vengeance; and you stand there and do nothing.” The Manager cannot act, nor can the actors and actresses, because Decima plays with them as if they were her puppets—nobody can prevent her from becoming the player queen.

In both plays—and in Yeats’s and Pirandello’s plays in general—the personaggio and the anti-self are truly exceptional, but at the same time oppressive and cruel characters thanks to their mask. This oppression gives rise to a kind of tragic theatre, based on the oppression of the weak and inert personas by the dominant and creative personaggios.

Sources: