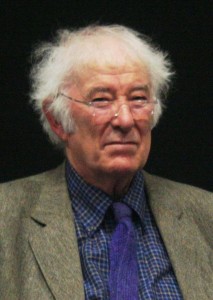

This year is the 100th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising. Honouring the uprising I have decided to compose an article in which I focus on one of the greatest figures of twentieth century Ireland, Seamus Heaney.

This year is the 100th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising. Honouring the uprising I have decided to compose an article in which I focus on one of the greatest figures of twentieth century Ireland, Seamus Heaney.

Died in 2013 at the age of 74, Heaney was considered a key figure in Irish poetry. Robert Lowell described him as “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”. The Independent went even further claiming that he was “probably the best-known poet in the world.” In 1995 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Not only was he a well-known poet, but also a playwright, translator, and lecturer. His translation of Beowulf (1999) won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award in 2000.

Let me turn away from his extraordinary talents now, and focus on his poems in which the motif of the bog and the feminine quality of Ireland construct the very essence of the work. Here is one of his descriptions of his memories in the foggy Ireland:

“When I was a child and an adolescent I lived among peat-diggers and I also worked in the peat bog myself. I loved the structure the peat bank revealed after the spade had worked its way through the surface of the peat. I loved the mystery and silence of the place when the work was done at the end of the day and I would stand there alone while the larks became quiet and the lapwings started calling, while a snipe would suddenly take off and disappear […]”.[1]

In an essay for Preoccupations he wrote:

“I have always listened for poems, they come sometimes like bodies come out of a bog, almost complete, seeming to

have been laid down a long time ago, surfacing with a touch of mystery.” (Heaney, 34)

Heaney tended to associate Ireland with feminine qualities; he has given mysterious power to the Irish soil. The ‘bogland’ appears an essential motif in his poems, representing the whole Irish landscape, through which one can find the very roots of Celticism. Additionally, the image of the bog is sometimes represented by Heaney as a goddess, as we can see it in his poetry collection Wintering Out and in another significant poem, “Tollund Man”.

The vulnerable femininity of Ireland appears in another famous poem “Act of Union”. Here Heaney represents Ireland as suppressed woman, who is raped by England, the representative of masculine qualities. Born in Northern Ireland, Heaney took the question of independence from the Empire very seriously. Composing such powerful and passionate poems as he did, he joined the long tradition of Irish poetry, representing Ireland as a suppressed nation suffocated by England. It seems as if Irish people wanted to live a life undisturbed by the English, but then the question remains: how should Ireland be defined then? After all, how can we define females if not in their relationship to males?

The vulnerable femininity of Ireland appears in another famous poem “Act of Union”. Here Heaney represents Ireland as suppressed woman, who is raped by England, the representative of masculine qualities. Born in Northern Ireland, Heaney took the question of independence from the Empire very seriously. Composing such powerful and passionate poems as he did, he joined the long tradition of Irish poetry, representing Ireland as a suppressed nation suffocated by England. It seems as if Irish people wanted to live a life undisturbed by the English, but then the question remains: how should Ireland be defined then? After all, how can we define females if not in their relationship to males?

[1] Seamus Heaney gave a talk at Silkeborg Museum in 1996, where he described his childhood memories of the bog. Source: https://bogbodies.wordpress.com/2012/03/15/the-tollund-man-seamus-heaney/

Sources

Heaney, Seamus. Preoccupations: Selected Prose. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1980. Print

Green, Carlanda. “The Feminine Principle in Seamus Heaney’s Poetry.” Critical Essays on Seamus Heaney. Ed. Robert F. Garratt. New York: G.K. Hall & Co., 1995. Print

Source of Images: Wikipedia britannica.com