Previously I discussed how the faun, both as emblem and topic of decadent art, is used to euphemise paedophilia in Lolita. If I were to continue that chain of thoughts, I’d say that the two facets of the novel’s central entity, the faun and Humbert, are interchangeable not only as characters in the plot, but also as narrators, since some chapters are written in full appreciation of the crimes committed, while in others, the narrator simply cannot understand/believe Lolita’s frustration or his own fault. From the very beginning one thing is made clear to the reader: Humbert is an unreliable narrator. His confession is a carefully construed distortion of events. The question is: to what purpose?

Marcus Amit sees Humbert’s rhetoric gliding between other-deception and self-deception. Other-deception occurs, when we are perfectly aware of reality, but we gain some advantage of deceiving others, so we ignore Grice’s maxim of quality. Self-deception occurs when we cannot make difference between reality and the story we deceive ourselves with. Humbert, as character, does both. He deceives many of the characters, most notably Charlotte, whom he marries to molest her daughter. Meanwhile, Humbert also deceives himself thinking that sedating Lolita would reduce the severity of his crimes. Both deceptions require a carefully construed version of events to fit their purpose. Every narrative has a rhetoric, since every story, when told, inevitably turns into someone’s narrative.

Amit claims that Humbert’s narrative employs both kinds of deception, constantly alternating and Humbert’s narrative becomes inconsistent. He uses his elegant frenchy erudite English to hide the plain and cruel nature of his deeds, while some fading traces of guilt and regret reveal that he’s aware of his distortion of reality. Yet, whenever the reader picks up on one of these clues, the narrator mentions absurd things, which suggest that he actually believes what he says and is therefore severely self-deceptive. Watching Lolita play tennis and lose despite her outstanding form, Humbert recognises that he damaged her psyche, but dismisses the idea, saying that to Lolita tennis is simply unimportant. This interplay between self-deception and other-deception distracts the reader from noticing what is actually euphemised, the focus is drawn from the what to the how.

In Kubrick’s Lolita, Humbert’s self-deceptive character dominates during most of the plot. As mentioned previously, his gaze transforms the child into a sexually-potent and desirable person (equivalent of the nymph). Even when he suspects that Lolita wants to escape him, he silences these thoughts as if is was only paranoia. When she runs away with Quilty, Humbert faces reality and has a trauma doing so. However, from that moment on, his deception is strictly other-deception.

In Kubrick’s Lolita, Humbert’s self-deceptive character dominates during most of the plot. As mentioned previously, his gaze transforms the child into a sexually-potent and desirable person (equivalent of the nymph). Even when he suspects that Lolita wants to escape him, he silences these thoughts as if is was only paranoia. When she runs away with Quilty, Humbert faces reality and has a trauma doing so. However, from that moment on, his deception is strictly other-deception.

When he visits Dolores three years later, he sees her as we do: pregnant, decaying and wasted. Then, after their chat, he tends to fall back into self-deception and begs her to go with him, but through pain he is disillusioned and gives her up for good. In the film, interface between self-deception and other-deception manifests in terrible pain, and the constant shifting between the deceptions draws the attention to Humbert’s pains from Lolita’s suffering. Who’s victimized after all?

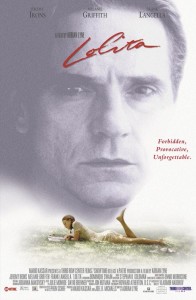

Sources of pictures: https://filmbalaya.files.wordpress.com/2010/06/lolita_ver4.jpg

http://nchollywood.com/lolita-1997/