In classical mythology, the faun became an emblem of lust (replacing the satyr) and raw instinct attracted to nymphs. Stéphane Mallarmé’s Afternoon of a Faun elaborates on this meaning through the recollections of a Faun – the lyric voice – woken from his afternoon nap and reflecting on his dream with nymphs.

In classical mythology, the faun became an emblem of lust (replacing the satyr) and raw instinct attracted to nymphs. Stéphane Mallarmé’s Afternoon of a Faun elaborates on this meaning through the recollections of a Faun – the lyric voice – woken from his afternoon nap and reflecting on his dream with nymphs.

In Nabokov’s Palace Márta Pellérdi dedicated a chapter to Lolita, where she discusses Nabokov’s use of the Faun and Nymph, relating Nabokov’s novel to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun. The latter literally makes a character of the Faun of Praxiteles. Nabokov’s Lolita is a bit more discrete in this matter, as the faun is enacted, this time, from literature. Pellérdi traces the character of Humbert back to the lyrical voice of Nabokov’s earlier poem, Lilith, already containing the idea of nympholexy. This poem, in turn, was inspired by Malarmé’s Afternoon of a Faun. Hence the main character’s genealogy from Malarmé’s poem via Claude Debussy’s musical Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun up to Nabokov’s Lilith. This is the metonymical link of cause and effect between Lolita and decadent art.

Pellérdi also notices a metaphorical link: Humbert is a decadent artist, in that, he extends the principle of art, aesthetics, outside art itself, to real life, where morals should dominate. Humbert makes enormous effort to integrate his immoral actions into an aesthetic: the long journeys, teaching Lolita tennis, trying to be her father, buying fancy clothes, giving her lots of money, etc. A raw sexual exploitation doesn’t necessitate such particulars. This surrendering of morals and reality for an aesthetic world makes Humbert a decadent artist, and turns his narrative into a decadent work broadening Mallarmé’s faun. Humbert calls himself a faun when talking about his attraction to Lolita: a nymphet. Pellérdi argues that these ‘transformations’ occur throughout Humbert’s narrative, because he cannot perceive the reality of his actions, but lives in a fairy-world, where pedophiles are fauns and twelve-year-old girls, nymphets. This ambiguity of character is extended to the narrator as well. The reader cannot be certain at any moment, whether the one who talks is the erudite Humbert or the lustful faun, because they’re used interchangeably in the entire narrative. The faun becomes a euphemism for pedophile excluded from both narrative and character.

Pellérdi also notices a metaphorical link: Humbert is a decadent artist, in that, he extends the principle of art, aesthetics, outside art itself, to real life, where morals should dominate. Humbert makes enormous effort to integrate his immoral actions into an aesthetic: the long journeys, teaching Lolita tennis, trying to be her father, buying fancy clothes, giving her lots of money, etc. A raw sexual exploitation doesn’t necessitate such particulars. This surrendering of morals and reality for an aesthetic world makes Humbert a decadent artist, and turns his narrative into a decadent work broadening Mallarmé’s faun. Humbert calls himself a faun when talking about his attraction to Lolita: a nymphet. Pellérdi argues that these ‘transformations’ occur throughout Humbert’s narrative, because he cannot perceive the reality of his actions, but lives in a fairy-world, where pedophiles are fauns and twelve-year-old girls, nymphets. This ambiguity of character is extended to the narrator as well. The reader cannot be certain at any moment, whether the one who talks is the erudite Humbert or the lustful faun, because they’re used interchangeably in the entire narrative. The faun becomes a euphemism for pedophile excluded from both narrative and character.

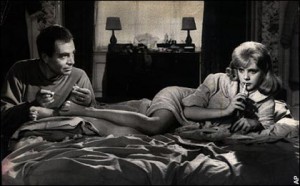

In Kubrick’s film the ‘fauny’ side of Humbert manifests mainly in his gaze. Lolita is almost never shown without Humbert staring at her. On the few occasions when she’s unmonitored, Dolly is a little brat running around. In Humbert’s presence, she becomes a gracious young woman: both her behavior in public and her position when sunbathing reveal sexual maturity. This is what Humbert sees, and we recognize the euphemistic gaze, betrayed by the woman’s playing with the hula- hoop, reading comics and other childish activities.

In Kubrick’s film the ‘fauny’ side of Humbert manifests mainly in his gaze. Lolita is almost never shown without Humbert staring at her. On the few occasions when she’s unmonitored, Dolly is a little brat running around. In Humbert’s presence, she becomes a gracious young woman: both her behavior in public and her position when sunbathing reveal sexual maturity. This is what Humbert sees, and we recognize the euphemistic gaze, betrayed by the woman’s playing with the hula- hoop, reading comics and other childish activities.

Decadent art is also present, especially in Quilty’s play The Enchanted Hunters, in which Lolita plays a nymph-like figure, and in a close-up we see Humbert’s face gradually distorting because of sexual desire: thus the nymph and faun emerge.

Sources of images: http://www.1st-art-gallery.com/(after)-Francois-Boucher/A-Satyr-Surprising-A-Sleeping-Nymph.html

http://drfreex.com/2012/04/23/the-stanley-kubrick-project-lolita/

http://wunderbuzz.co.uk/cinema/the-woman-behind-lolita/