In Moldova apparently there has always been a cultural duality or rather a cultural tension since it became a modern state-entity: first as member state of the Soviet Union, than, from 1991, as an independent state. While a member of the Soviet Union, Moldova and its local culture were subdued to the Russian influence. This is proven by the fact that in libraries, especially poorly equipped ones, even today many older editions of western literature, even some French comics, are available only through the prism of (Russian) language, (Cyrillic) alphabet and (communist) ideology of the dominant culture. The last aspect is marked by the trace of censorship I noticed in case of older French comics.

In Moldova apparently there has always been a cultural duality or rather a cultural tension since it became a modern state-entity: first as member state of the Soviet Union, than, from 1991, as an independent state. While a member of the Soviet Union, Moldova and its local culture were subdued to the Russian influence. This is proven by the fact that in libraries, especially poorly equipped ones, even today many older editions of western literature, even some French comics, are available only through the prism of (Russian) language, (Cyrillic) alphabet and (communist) ideology of the dominant culture. The last aspect is marked by the trace of censorship I noticed in case of older French comics.

More recently, beginning from 1991, the orientation towards Western Europe through the EU gained ground. Relations to the west are mediated by Romanian culture which is much closer to Moldova than the Russian, since Romania and Moldova share many key historical/cultural moments and personalities. Yet, Romanian mediation still imposes a foreign ideology and language variety on Moldavian culture.

This concerns comics in two ways: firstly, the language of comics in Moldova is standard Romanian and secondly, Moldavian authors are represented as integral to Romanian mainstream literature (see the Hungarian and Romanian Wikipedia on Ion Creangă), ignoring their adherence to a different culture, society and (in part) state.

Ion Creangă, a famous writer (especially of short prose) and one of the Romanian classics, lived, thought and wrote on the territory of Moldova during the second half of the 19th century.

The Modern Romania, as we know it, did not exist, and Creangă’s work revolved entirely around Moldavian culture and narratives.

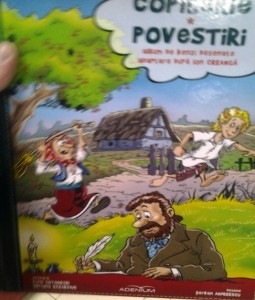

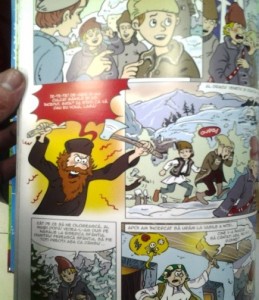

His most famous work, the autobiographical novel Amintiri din Copilărie (Childhood Memories) has been adapted into comics-format in 2013 published by Adenium (a prestigeous Romanian publishing company located in Iaşi). This adaptation presents a rather incomplete, altered image of the Moldavian society represented originally. At best, the adaptation aims at the proximation of the work to contemporary Romanian society, at worst, it is a distortive discourse undermining the specific characteristics of an individual culture. This comic-appropriation is widely sold and read in Moldova: all children’s libraries have it, some teachers and tutors use it and all book stores promote it on the front shelves.

Gheorghe Vîrtosu, who was born and raised in Moldova, unlawfully left the state and moved to France at the age of 17-18. There, he got indulged into doubtful businesses which involved the purchase of real estates in Britain, but also traffic in persons (smuggling east European prostitutes to Britain and France). His business was discovered when he was charged with fraud and tax evasion. Eventually, he was sentenced to eight years of prison in France.

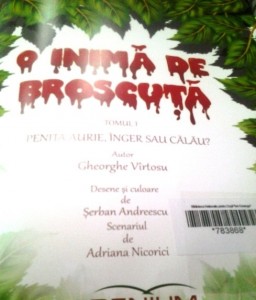

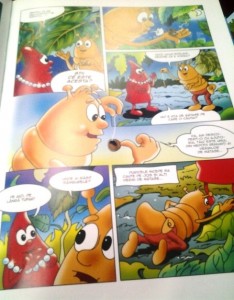

Gheorghe Vîrtosu, who was born and raised in Moldova, unlawfully left the state and moved to France at the age of 17-18. There, he got indulged into doubtful businesses which involved the purchase of real estates in Britain, but also traffic in persons (smuggling east European prostitutes to Britain and France). His business was discovered when he was charged with fraud and tax evasion. Eventually, he was sentenced to eight years of prison in France.  Once imprisoned, he started writing his famous comics series for children, O inimă de Broscuţă (A Little Frog’s Heart).

Once imprisoned, he started writing his famous comics series for children, O inimă de Broscuţă (A Little Frog’s Heart).

These comics, published also by Adenium (in 2011), are very successfull and widely-sold both in Romania and in Moldova.

However, very little can be found on the author (after extensive research, including newspapers from the Republic of Moldova, I only came up with the above stated info).

Even the fact that he is Moldavian is mostly unknow (I accidentally found out while talking to a librarian), to the wide audience he is French-based successfull Romanian comic-artist/businessman.

Sources of images: http://www.mythweb.com

Images taken by Nemes Zsolt